I was reading some Nietzsche recently, as one does, and it struck me that his analysis of Greek culture could have immediate relevance to the most notable modern re-configuration of mythology, namely George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire book series. Whether it was a happy accident or divine illumination, I cannot say, and I suppose that doesn’t matter. What matters is that I noticed it and am articulating it with you.

Recent scholarship of the book series found on the ASOIAF forums and the asoiaf sub-reddit have shown that GRRM has secretly but deliberately created a synecdoche of mythology in his fantasy world, featuring heroes, villains, dragons, prophecy and resurrection as key drivers of the narrative.

While the plotline specifics of this story are all Martin’s, the symbols and themes underlying the story are ancient and even primordial. They represent truths hidden behind the artifices of our modern culture such as modern science, skepticism and logic. These truths are the IRL old gods inherent in both nature and our innermost psyche that reveal themselves through various revelation, such as dreams or hallucinogenic episodes.

In this essay, I will attempt to interpret Nietzsche’s thesis that dramatic tragedy is the synthesis of the two primary traditions of the ancient Greek art forms, the Apollinian and the Dionysian, and how this synthesis manifests itself through song. Then I will select two major archetypes revealed in the story of ASOIAF and show the relationship to this Greek tragedy model. Finally, I will try to illustrate how these archetypes merge and underlie the Martin’s grand epic.

Narrative sequences in most stories can be broadly defined as a comedy or tragedy. By comedy, I don’t mean “ha-ha” comedy, but rather a story that is redemptive, one with a relatively happy ending, or one where the protagonist ends up in a position equal to or higher than they were before. The scholar Northrop Frye describes the narrative shape of comedy as a “U”:

If we look at a comedy, we find that a situation is presented which gradually becomes more ominous and threatening and foreboding of disaster to the characters with which we are all sympathetic. Then there’s a kind of gimmick or sudden shift in the plot, and eventually it moves toward a happy ending where everybody gets married, and the hero and heroine’s real life is assumed to being after the play is over. That is why the heroes and heroines of so many comedies are in fact rather dull people. The main character interest is thrown onto the blocking characters, the parents who’ve forbidden them to marry, for instance.

Frye goes on to note that the Bible itself is the supreme comedy. It starts, essentially, with the birth of Man in Eden, his downfall, and then, thousands of pages later, the redemption of Man on the cross. In between there are dozens of other fall and resurrection stories, involving kings, prophets, poor ol’ Job, etc. It’s why Dante called his epic poem The Divine Comedy.

The Greeks were different, as Frye points out:

We owe our great tragedies very largely to the Greek tradition, which has a different outlook. The Bible is not very close to tragedy: when it deals with disaster, its point of view is ironic rather than tragic. While there are many reasons for this, the main one is that in a typical tragedy there is a hero who embodies certain qualities which suggest the superhuman, and the Bible recognizes no such hero except for Jesus himself. The Crucifixion would be the one genuine tragic form in the Bible, but that of course is an episode in a containing comedy.

In other words, if comedy is a “U”, tragedy is a backwards “N”.

In all of the main story of ASOIF, I can recall only one main character who has had a positive redemptive arc, that being Sandor Clegane. He went from a being a tortured soul, angry and resentful at the world, then became broken, but ended up with a realistic opportunity at attaining internal peace on the Quiet Isle, if you subscribe to the Gravedigger theory. Therefore, the Hound’s tale is comedic, and I for one am happy that it is so. (I may be in the minority in hoping that Cleganebowl never emerges its ugly head.)

Other than that, the intertwining stories being told don’t bode well for the rest of characters. It’s tragedy through and through, and even if some characters manage to survive and defeat the evil emerging from the north or underseas, it will come at a significant cost. A Song of Ice and Fire is textbook tragedy.

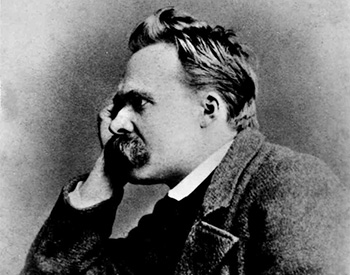

Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy

The opening lines of Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy lay out his thesis quite starkly:

We shall have gained much for the science of aesthetics, once we perceive not merely by logical inference, but with the immediate certainty of vision, that the continuous development of art is bound up with the Apollinian and Dionysian duality—just as procreation depends on the duality of the sexes, involving personal strife with only periodically intervening reconciliations. The terms Dionysian and Apollinian we borrow from the Greeks, who disclose to the discerning mind the profound mysteries of their view of art, not, to be sure, in concepts, but in the intensely clear figures of the their gods. Through Apollo and Dionysus, the two art deities of the Greeks, we come to recognize that in the Greek world there existed a tremendous opposition, in origin and aims, between the Apollinian art of sculpture, and the nonimagistic, Dionysian art of music. These two different tendencies run parallel to each other, for the most part openly at variance; and they continually incite each other to new and more powerful births, which perpetuate an antagonism, only superficially reconciled by the common term “art”; till eventually, by a metaphysical miracle of the Hellenic “will,” they appear coupled with each other, and through this coupling ultimately generate an equally Dionysian and Apollinian form for art—Attic tragedy.

Nietzsche posits that the primary contrast between the two art forms comes from their respective inspirations, namely the Apollinian dream and the Dionysian intoxication. These two inspirations are distinct yet mutually reinforcing when combined in the Greek tragedy, and as such, the tragedies of Western art and literature have retained this symbiotic relationship to this day.

To understand this concept, however, one must understand what is meant by Apollinian and Dionysian.

The Sun of God

There’s no point in creating a new introduction of the concept of the Apollinian dream when Nietzsche does it so much better:

This joyous necessity of the dream experience has been embodied by the Greeks in their Apollo: Apollo, the god of all plastic energies, is at the same time the soothsaying god. He, who (as the etymology of the name indicates) is the “shining one,” the deity of light, is also ruler over the beautiful illusion of the inner world of fantasy.

Phoebus Apollo was born of Leto, a twin of Artemis, and son of Zeus. He’s associated with the all-seeing Sun (though Helios is the sun proper). Because of his ability to see everything, he is the patron of prophesy and, because of that ability to see everything to come, he knows what will heal and what will destroy. As such, he is also the god of both healing (he is the father of Asclepius, the god of medicine, and Hygieia, or “health”) and pestilence. He is the apotheosis of the dream and internal revelation.

Greeks worshipped him for his patronage of logic, reason and music. He is portrayed as a handsome youth, beardless and well-dressed, and often crowned with a halo. He is symbolized by the laurel, the lyre, the bow and arrow, and the white raven.

The slopes of Mount Parnassus was home to the most famous seer in history, Pythia, aka the Oracle of Delphi. Ancient legend had it that Apollo won the the oracle by slaying Python, the terrible dragon serpent and son of Gaia. Renowned throughout the Greek world, petitioners travelled far and wide to Delphi to hear the cryptic—and often ironic—prophecies, hoping for good news and generally just hearing what they wanted to hear.

Like soothsayers from virtually all other cultures and times, seers guided by Apollo united the inner and outer worlds together through heightened awareness, revelation of hidden meanings, communication of profound information and healing.

Although they are not his offspring, Apollo leads the nine Muses, goddesses of music, poetry, dance, theatre, history and astronomy. He himself is lyrist of the Olympus, as shown in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo:

Apollo plays on his lyre, to lead the dance and the singing,

while glory shines all about from his robe and his dancing feet.

Leto of golden hair and Zeus, designer of counsel,

rejoice as they watch their dear son laying amid the immortals

The oral poet of Ancient Greece carried and communicated knowledge through the lyrical stories, which spread the lessons of the gods, especially the importance of prudence and reason. The lyrical poem had meaning. It imparted wisdom and logic on the listener in a way that could be easily digested and repeated to others.

Apollo therefore represented the supremacy of order and reason over barbarism and illogic. He was the “Hellenic spirit,” revered by Socrates and the philosophers. Alexander the Great claimed to be a son of Zeus, and he had images and statues of Apollo modelled after himself (the halos of which persist to this day in Christian iconography). Apollo symbolized the noble, progressive values of the Greek nation, and remained the preeminent deity for enlightenment thinkers during the European renaissance over a thousand years following the demise of the Greek empire. His was the triumph of science over the wild unknown, the internal vision over externally generated ecstasy.

Naturally, Nietzsche considers Apollo overrated. He considers the consciousness attributed to the god of light to be a “veil of māyā” (i.e. “illusion” in Sanskrit) which masks the reality of nature. In essence, Apollo is the artistic antithesis of Dionysus.

The God of Fun

Son of the immolated Semele, native to the thigh of Zeus, twice-born Dionysus is the beloved god of wine and earthly vitality. To the Greeks, he is the masculine fertility deity, corresponding to Bacchus, the Horned Lord and the Green Man, and acts as a masculine counterpart to Demeter and other Great Mother archetypes. He is symbolized by the phallus and bull’s horns, as well as wreaths of ivy and staff of thyrsus, and is the central figure of a nature-worshipping, madness-inducing cult of ecstasy.

Etymologically, Dionysus may have been derived from the words “dios” (god, or derived from Zeus) and “Nysos” (from the city of Nysa, which in turn was traditionally named after Dionysus’s nurse). From birth, he had been hidden from Hera’s jealous rage with the nymphs of Nysa (the nysai) until he came of age when Zeus recruited him to sit on an Olympian throne. He rides into Olympus on the back of an ass, serenaded by an intoxicated chorus and escorted by a orgiastic promenade of feral beasts, satyrs and nymphs. He is truly a wild and crazy guy.

Like Demeter, Dionysus’s rescue of his mother from Hades signifies his association with death and rebirth. This also links him to other deities of the underworld, such as Osiris and Odin, and as such, Dionysus is similarly linked to the wisdom of the mysteries of suffering and existence. As such, wherever Dionysus goes, he may simultaneously bring frivolity or madness, life or destruction, to his worshippers or detractors or both, just as nature itself can bring forth bounty or famine regardless of our devotion. Like nature, he is fickle and defies interpretation; Dionysus is the antithesis of reason, the apotheosis of emotion, and the encapsulation of life and death.

Walter Otto in his book Dionysus: Myth and Cult notes as much:

The fullness of life and the violence of death are equally terrible in Dionysus. The Greek endured this reality in its total dimensions and worshipped it as divine.

Nietzsche admires Dionysus and thinks of his companions as portraying the true essence of Man:

The satyr, like the idyllic shepherd of more recent times, is the offspring of a longing for the primitive and the natural; but how firmly and fearlessly the Greek embraced the man of the woods, and how timorously and mawkishly modern man dallied with the flattering image of a sentimental, flute-playing, tender shepherd! Nature, as yet unchanged by knowledge, with the bolts of culture still unbroken—that is what the Greek saw in his satyr who nevertheless was not a mere ape. On the contrary, the satyr was the archetype of man, the embodiment of his highest and most intense emotions, the ecstatic reveler enraptured by the proximity of his god, the sympathetic companion in whom the suffering of the god is repeated, one who proclaims wisdom from the very heart of nature, a symbol of sexual omnipotence of nature which the Greeks used to contemplate with reverent wonder.

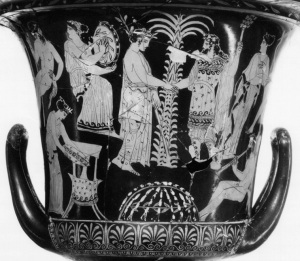

Theatre played an important role in the worship of Dionysus, starting in the sixth century before Christ. The Lanaea (the festival of the Maenads) occurred in the Athenian spring and featured tragedies at the amphitheatre. During the following century, the City Dionysia would be performed at the Theatre of Dionysus near the Acropolis, featuring three tragedies and a satyr comedy.

Choruses in the tragedies were based off the dithyramb, which was initially a hymn to Dionysus and then later a tribute to a tragic hero. Aristotle thought that the original dithyrambs were performed by a chorus of goat-legged satyrs, and so these songs were referred to as tragoidia, or “goat songs,” hence the term “tragedy.” Whatever their origin, the form of tragedy emerged in Greek culture when heroes stopped being depicted in the third-person and started being sung in the first-person by the chorus.

Thus spake Nietzsche:

In the Dionysian dithyramb man is incited to the greatest exultation of all his symbolic faculties; something never before experienced struggles for utterance—the annihilation of the veil of māyā, oneness as the soul of the race and of nature itself.

Psychologically, to be entranced with Dionysus is to be attuned to the natural world, including all the beauty, ecstasy, harshness and suffering that may entail. We accept our innate id, and go where our emotions and desires take us. It’s the feeling you get at a particularly enticing rock concert, or as you you cry during a sad movie, or when you scream on a roller coaster, or trip out on a hallucinogenic drug, or fall in love for the first time. It’s raw and powerful and chaotic and expressive. It’s no wonder the Dionysian cult was so popular in its time. Or today, for that matter, as seen at events like Burning Man.

But too much of the Dionysian world can also be very destructive, regardless of the potential creativity it may inspire. Tragedy requires the complementary Apollinan sense of ego—logic and order and divine consciousness—so as to be truly profound and meaningful.

The Birth of Tragedy

Nietzsche says “that tragedy arose from the tragic chorus, and was originally only chorus and nothing but chorus” because “the tragic chorus of the Greeks is forced to recognize real beings in the figures on the stage.” The chorus, often comprised of devotees to Dionysus, was used to provide the emotional resonance for a scene and to establish the themes and motivations of the tragic hero portrayed, driven from the characters’ base desires and vitality.

But to provide a lesson, tragedy needs more than emotions and theme. You can’t just sit watch a bunch of exotic nuts run around and dance and scream and get enthralled in nature. That’s about as exciting as watching a couple of stoners jive on life. No, for true profundity or meaning, you need structure, setting, plot, dialogue—these are the realms of Apollo.

As such, in addition to the chorus, Greek tragedy evolved to include dialogue between two or more major characters and follow a logical, discernible pattern. This is Nietzsche’s theory, that tragedy required a Dionysian ideal (in the Platonic sense) to be transformed by Apollo into an understandable or relatable manner for the Greek audience:

Using Plato’s terms we should have to speak of the tragic figures of the Hellenic stage somewhat as follows: the only truly real Dionysus appears in a variety of forms, in a mask of a fighting hero, and entangled, as it were, in the net of the individual will. The god who appears talks and acts so as to resemble an erring, striving, suffering individual. That he appears at all with such epic precision and clarity is the work of the dream-interpreter, Apollo, who through this symbolic appearance interprets to the chorus its Dionysian state. In truth, however, the hero is the suffering Dionysus of the Mysteries, the god experiencing in himself the agonies of individuation, of whom wonderful myths tell that as a boy he was torn to pieces by the Titans and now is worshipped in this state as Zagreus. Thus it is intimated that this dismemberment, the properly Dionysian suffering, is like a transformation into air, water, earth, and fire, that we are therefore to regard the state of individuation as the origin and primal cause of all suffering, as something objectionable in itself.

This is important because truth, above all else, is recognition of the Dionysian suffering—man’s suffering—and tragedy is, at its heart, the story of this suffering. In fact, Nietzsche reveres truth as a goddess in and of itself:

The philosophy of wild and naked nature beholds with the frank, undissembling gaze of truth the myths of the Homeric world as they dance past: they turn pale, they tremble under the piercing glance of this goddess—till the powerful fist of the Dionysian artist forces them into the service of the new deity. Dionysian truth takes over the entire domain of myth as the symbolism of its knowledge which makes known partly in the public cult of tragedy and partly in the secret celebrations of dramatic mysteries, but always in the old mythical garb.

Where the Apollinian and Dionysian art come together most readily is, as you may have guessed, through music. By coupling the enlightened lyric from Apollo with Dionysus’s satyr chorus, the Greek tragedy is born in song:

What power was it that freed Prometheus from his vultures and transformed the myth into a vehicle of Dionysian wisdom? It is the Heracleian power of music: having reached its highest manifestation in tragedy, it can invest myths with a new and most profound significance. This we had already characterized as the most powerful function of music.

What troubles Nietzsche above all else, and what inspired his essay, is that the power of the myth has been diluted over time through the illusion—the māyā— of science and reason, and its wisdom can only be reinvigorated through a re-embrace of Dionysus:

For it is the fate of every myth to creep by degrees into the narrow limits of some alleged historical reality, and to be treated by some later generation as unique fact with historical claims: and the Greeks were already fairly on the way toward restamping the whole of their mythical juvenile dream sagaciously and arbitrarily into a historico-pragmatical juvenile history. For this is the way in which religions are wont to die out: under the stern, intelligent eyes of an orthodox dogmatism, the mythical premises of a religion are systematized as a sum total of historical events; one begins apprehensively to defend the credibility of the myths, while at the same time one opposes any continuation of their natural vitality and growth; the feeling for myth perishes, and its place is taken by the claim of religion to historical foundations. This dying myth was now seized by the new-born genius of Dionysian music; and in these hands it flourished once more with colors such as it had never yet displayed, with a fragrance that awakened a longing anticipation of a metaphysical world.

The Dionysian mythos provides the moral substrate of the Apollinian rationality. While the latter can provide context to the former, NIetzsche’s claim and greatest fear is that the elimination of the former by the latter can lead to the annihilation of both, to our peril.

In other words, myth is real while our perception is the illusion. We blind ourselves to the evolution of our psychology and what makes us human, what makes a moral life and a successful society. We are delusional in thinking that we can eliminate the reality while maintaining the illusion; the illusion can only exist with the reality of this mythology. Apollo cannot be transcendent without transcending to the unknowable, to Dionysus. We need both.

Now, given that you’ve gone through all that, what is the link between this theory and A Song of Ice & Fire?

In short, it’s R+L=J.

The Sun of the Dragon

“Will you make a song for him?” the woman asked.

“He has a song,” the man replied. “He is the prince that was promised, and his is the song of ice and fire.” He looked up when he said it and his eyes met Dany’s, and it seemed as if he saw her standing there beyond the door. “There must be one more,” he said, though whether he was speaking to her or the woman in the bed she could not say. “The dragon has three heads.” He went to the window seat, picked up a harp, and ran his fingers lightly over its silvery strings. Sweet sadness filled the room as man and wife and babe faded like the morning mist, only the music lingering behind to speed her on her way.

For a character with but two spoken lines in the entire five-book series to date, and one of those was revealed in a hallucinogenic vision no less, very few characters in ASOIAF have as much impact on the present-day narrative than Rhaegar, scion of House Targaryen, would-be king and the Last Dragon who died on the banks of the Trident by the war hammer of Robert Baratheon 14 years before the events in A Game of Thrones.

Much has been written about Rhaegar, particularly in the past six or seven years since the launch of the Game of Thrones television series, so I will not re-tread trodden trails any more than I must. For a very good and recent write-up on Rhaegar, I direct you to this excellent post at Watchers on the Wall, which includes information taken from the HBO series as well as published book material. I’ll try to reiterate only that information germane to this essay.

Rhaegar was born in tragedy, just outside the terrible destruction at Summerhall, the son of a soon-to-be-mad king, great-grandson of an dream-obsessed one. By all accounts, he was an exceptional child and man, good at everything, musically gifted, learned, bound to his education and duty, not to mention other-worldly handsome. He reminds me a lot of myself, to be honest.

As you might have guessed, Rhaegar features many similar characteristics to Apollo, and thus they share a similar archetype, though GRRM has taken care not to make them completely interchangeable. For one thing, Rhaegar is not a god, but merely god-like. But they have enough in common to make a comparison worthwhile.

Starting off, both Rhaegar and Apollo are exalted sons of their king, epitomizing the noble, aristocratic ideal for an entire nation. They are both princes of light, and symbolize solar figures within their own mythology.

“The dragon prince sang a song so sad it made the wolf maid sniffle.”

And then there is Rhaegar’s Apollinian association with the harp. They both embody the artistic archetypes in using song to reverberate the heart while still expressing a story of meaning. It is just as likely that Rhaegar would have been a tremendous poet or dancer or storyteller, for Rhaegar did all things well, but that he is particularly known as a lyrist provides a significant divine Apollinian resonance to A Song of Ice and Fire.

“As a young boy, the Prince of Dragonstone was bookish to a fault. He was reading so early that men said Queen Rhaella must have swallowed some books and a candle whilst he was in her womb. Rhaegar took no interest in the play of other children. The maesters were awed by his wits, but his father’s knights would jest sourly that Baelor the Blessed had been born again.”

The god of logic and science would have been proud to see such dedication to education in the dragon prince at such a young age. With knowledge, the intelligent can learn what can be done, and with intelligence, the wise might even learn what should be done.

”Until one day Prince Rhaegar found something in his scrolls that changed him.”

Unlike the Titan Prometheus, who could actually look into the future (likely due to his mother being Gaia herself), Apollo’s foresight seems to be based on observing signals and interpreting them. This explains Apollo’s relationship with the oracle, who was notoriously vague about the fortunes told to seekers of wisdom.

It is clear that the obviously intelligent Rhaegar did all he could to learn about the world through past insights from scholars and legends, and that through his perspicacity he was prompted to take action. Was this that which inspired him to take the actions he did? Did he do the right thing?

And from whence did this wisdom originate?

The Nymph of the Laughing Tree

“No one knew,” said Meera, “but the mystery knight was short of stature, and clad in ill-fitting armor made up of bits and pieces. The device upon his shield was a heart tree of the old gods, a white weirwood with a laughing red face.”

Ah, Lyanna. The better half of the enduring ASOIAF mystery. What can you say about the half-centaur she-wolf mystery tourney knight which hasn’t been said already? Again, I’ll point you to JoeMagician’s excellent summary of Lyanna at Watchers on the Wall.

The third-born child of Lord Rickard Stark, Lyanna grew up wild and free in her Winterfell home. Her analog is Arya, in looks and in temperament. She’s a tomboy rapscallion, preferring horses and swords to gowns and needlework. “She had the wolf blood,” says Ned, illustrating her feisty, stubborn independent streak.

Despite (or because of) her disposition, Lyanna appears to have been well-loved by her siblings. Meera’s tale of the Knight of the Laughing Tree made clear the nature of Lyanna. She exuded justice with her defence of little Howland Reed against the three dipshit squires at the tourney of Harrenhal. She was honourable when she invited the crannogman to the bench at the feast. She was courageous when she donned armor as a mystery knight to tilt against seasoned jousters. She revealed her caring nature while weeping tears during Rhaegar’s performance on the harp (though she also showed her excessive pride when she reacted to Benjen’s mocking of said tears).

Ned thought her beautiful, and there is no reason to doubt this; however it seems that hers was a less than conventional beauty. Cersei Lannister certainly didn’t have much to say about Lyanna other than calling her an “insipid little dead sixteen-year-old.” It is far more likely that the young wolf maiden emanated beauty through her vivacious spirit.

Most importantly, she is the type of girl who would throw off her engagement to run away with a married man, instigating a civil war and bloody revolution.

And how she smiled and how she laughed,

the maiden of the tree.

She spun away and said to him,

no featherbed for me.

I’ll wear a gown of golden leaves,

and bind my hair with grass,

but you will be my forest love,

and me your forest lass

There is no doubt that Lyanna evokes a earth-spirit vibe in her character with her love of horses and not being afraid to get a little messy. That her sigil is a laughing weirwood confirms that she is a tree person, as shown in the essay “It’s an Area Thing” by Lucifer means Lightbringer.

The symbolism here is what we are looking at, and the suggestion here is that the Knight of the Laughing Tree might be a green man. I think we are certainly led to imagine the green men, these “guardians” as Bran thinks of them, as some sort of warrior-like beings tied to the weirwoods, so the comparison makes a certain amount of sense. When you consider the weirwood face device on the mystery knight’s shield, it seems obvious that, symbolically, we are dealing with yet another version of the tree-emanation figure, very like Jaquen or Ghost or many of our Nissa Nissa reborn figures.

Nissa Nissa, of course, being the sacrificed wife of the legendary Amor Ahai. LmL helpfully points out the possible etymology of Nissa Nissa:

Nissa is a Norwegian word, which means “helpful elf” or “michevious elf.” It’s a well known word in Scandinavian countries, a part of their Christmas lore, so when we consider the large influence of Norse mythology on the books, it seems likely George is aware of this meaning, and may first heard of it in this context. Nisha is a not-uncommon Vedic Sanskrit female surname which means “night,” while in Arabic it just means “woman.” In addition to Norse myth (and many others), George has also pulled some ideas from the Hindu legends of the Vedas, so it’s likely he is aware of these translations of Nisha as well. That’s pretty good so far – the moon is certainly a “night woman,” and you could see a moon as a kind of “elf planet,” a smaller version of a planet. Nissa Nissa helped to forge Lightbringer, but I wonder, was this a helpful act, or an act of mischief? We’ll have to see if we can figure that out.

However, as I noted earlier, nymph followers of Dionysus were called “nysai.” There is not a clear etymological link between nysai and nissa, but that doesn’t matter because, given all this, it seems clear that Lyanna does represent the more ancient, organic, wild Dionysian wisdom of the Greek tragedy equation, and can be considered a part of the Dionysian retinue.

“Love is sweet, dearest Ned, but it cannot change a man’s nature.”

Lyanna possesses a wisdom that surpasses her teenage years. It is the sort of wisdom that isn’t logical—why would anyone consider a teenage girl entering the lists against stronger, more experienced knights to be a logical idea?—but one which informs her to do what is morally right in defence of the honour of a noble house.

In the same way, she recognizes the folly in believing that Robert Baratheon could be anything more than a manic, lustful brute. She understands the stag lord’s nature—his being—even if her loving brother fails to do so himself.

In these ways, it’s clear that she is listening to her heart, or maybe to the old gods in the heart trees, which might be the same thing.

“Ah, damn it, Ned, did you have to bury her in a place like this?” His voice was hoarse with remembered grief. “She deserved more than darkness …”

“She was a Stark of Winterfell,” Ned said quietly. “This is her place.”

“She should be on a hill somewhere, under a fruit tree, with the sun and clouds above her and the rain to wash her clean.”

“I was with her when she died,” Ned reminded the king. “She wanted to come home, to rest beside Brandon and Father.”

You can see the conflict here, the king of summer arguing with the king of winter on the proper place for the wild tree nymph. It’s certainly a Persephone motif and, as noted above, Dionysus has many parallels with Demeter with respect to the concept of entering Hades to prompt the changing of the seasons. And, despite the objections of Demeter (i.e. Dionysus), Persephone belongs in Hades as much as she does on a hilltop under the tree and sun and rain.

As such, one cannot deny that Lyanna represents the Dionysian archetype in her brief story, just as much as she represents the Hadean Starks.

Imagine the tragedy that would ensue should she ever merge with her Apollinian counterpart.

A Tragedy of Ice & Fire

At the welcoming feast, the prince had taken up his silver-stringed harp and played for them. A song of love and doom, Jon Connington recalled, and every woman in the hall was weeping when he put down the harp.

There’s little reason to believe that Rhaegar Targaryen kidnapped and raped Lyanna Stark as she traveled to Riverrun for her brother’s wedding. The more likely story is this: Rhaegar first became acquainted with Lyanna at or near Harrenhal, when he was tasked to discover the identity of the Knight of the Laughing Tree. They may have met long enough to make a serious connection, which meant that it was almost instantaneous. To what degree, no one knows, but Rhaegar confirmed his commitment to her the moment all the smiles died when he presented her the (Apollinian) laurel of blue roses. A few weeks or months later, on the road to Riverrun, Lyanna disappeared, and her brother claimed that she was taken by Rhaegar. Again, there is a gap in the story, but it is likely that they went back toward Harrenhal, to the God’s Eye lake, and were married in front of a weirwood on the Isle of Faces, maybe even in the presence of the green men (of whom Lyanna would have been aware, given that she had spent a night feasting with Howland Reed). Note that it is unlikely that Rhaegar’s marriage was annulled by a septon as in the GoT series. Then they took off, travelling a couple thousand miles maybe, somehow avoiding detection despite the fact that Rhaegar’s Valyrian features and noble demeanour would have made him instantly recognizable anywhere in the Seven Kingdoms. They found their way to the Tower of Joy in Dorne. Lyanna got knocked up before Rhaegar rode off to war and his impending doom. Jon Snow was born, Lyanna died, and Ned lied.

And that’s the story of how R plus L equals J.

To understand why this matters, you need to look at how it began, and to do that, you need to look at the motivations of the Apollinian Rhaegar.

Rhaegar’s association with Apollo seems paradoxical when one considers that Apollo, the Hellenic lord of light, destroyed the dragon Python at Delphi. However, the Pythian dragon is that of the earth-mother Gaia, representing the primordial chaos that begets the creation and destruction of all. By slaying the dragon, Apollo asserts the triumph of the Greek’s preferred state of being—logical, order-driven and scientifically enlightened. When Apollo slayed the dragon, he caused the death of the earthly god, just as in our world, Nietzsche proclaimed (regretfully, it should be noted) the death of our own God.

In this sense, did the choices and actions of Rhaegar-as-Apollo slay Rhaegar-as-dragon? Was his entire purpose meant to destroy himself to bring apart a new order, or to regain the mystical Dionysian truth? Did Rhaegar commit suicide by revolution? Possibly, but it goes deeper than that.

Remember who you are, what you were made to be. Remember your words.

“Fire and blood,” Dany told the swaying grass.

Dragons may have been present on Planetos since the Great Empire of the Dawn, or at least they have appeared and disappeared on the earth in that period. Their bones are discovered everywhere, far beyond the Valyrian heartland in places where they simply should not be found. With the Doom of Valyria, the dragon population was severely curtailed, reaching a false renaissance during the Targaryen dynasty. Following the calamitous civil war known as the Dance of the Dragons, Westerosi dragons were imprisoned within the Dragonpit in King’s Landing. Those dragons never achieved the might and terror held by their predecessors; the last few dragons were stunted and weak, and they all had died out by 153AC during the reign of Aegon III.

Marwyn the Mage claimed the demise of the dragons was a deliberate attempt by the Citadel to extinguish the incredibly dangerous flames of these magical beings, and it is understandable to believe this. But it could also be argued that the Targaryens allowed this to happen in exchange of retaining the Iron Throne. After all, when you are the authority of law and order, the last thing you need is the means to generate vast chaos in the realm, as evidenced by the Dance of Dragons. Danaerys paid the same price in Meereen to her chagrin. The Citadel had its influence, but ultimately the dragonlords were responsible for he fate of their brood.

Regardless of the root cause of their demise, in only a few short years, most people were relegated to the fact that magic had disappeared from the world. Tyrion mocks the very idea of magic, while every learned individual, particularly the maesters, will tell you that the dragons had all died out and magic with it.

Magic had died in the west when the Doom fell on Valyria and the Lands of the Long Summer, and neither spell-forged steel nor stormsingers nor dragons could hold it back, but Dany had always heard that the east was different.

Nietzsche thinks that that magic is a form of the unknowable knowledge of our deep psychosis and was embedded in nature, and is thus Dionysian:

Under the magic of the Dionysian, not only does the bond between man and man lock itself in place once more, but also nature itself, no matter how alienated, hostile, or subjugated, rejoices again in her festival of reconciliation with her prodigal son, man. The earth freely offers up her gifts, and the beasts of prey from the rocks and the desert approach in peace. The wagon of Dionysus is covered with flowers and wreaths; under his yolk stride panthers and tigers.

Therefore, when magic dies out, then mankind is no longer connected to the unutterable profound of our very being. We become lost, our societies arbitrary, our morality unfounded. We are unwise and so we cannot fully comprehend our suffering nor the pleasure attuned during the struggle to overcome this suffering.

Just because we don’t understand this doesn’t mean the world has stopped torturing us with its brutal fury. Our being has evolved to protect ourselves from the wroth of the primordial chaos and to prosper out of it; however once we forget who we are, then we are at the mercy of the corrupt tyranny.

Enter the Others.

”In that darkness, the Others came for the first time,” she said as her needles went click click click. “They were cold things, dead things, that hated iron and fire and the touch of the sun, and every creature with hot blood in its veins. They swept over holdfasts and cities and kingdoms, felled heroes and armies by the score, riding their pale dead horses and leading hosts of the slain. All the swords of men could not stay their advance, and even maidens and suckling babes found no pity in them. They hunted the maids through frozen forests, and fed their dead servants on the flesh of human children.”

Yeah, serious stuff. All this had been dismissed as pure nonsense by bien pensants of Westeros and beyond, yet we as readers see the Others in the very prologue of A Game of Thrones.

I don’t believe that Rhaegar uncovered information specifically about this army of the dead in the scrolls, but he certainly foresaw enough to know that he would be playing a vital role in the unknowable yet inevitable disaster to come. To prepare this, he had to re-merge the Apollinian with the Dionysian of his world so that they could remember how to fight this threat. It could very well be that the revelation of the true personage of the Knight of the Laughing Tree was the moment Rhaegar realized the critical path he had to take.

With the marriage of Lyanna to Rhaegar, the forgotten knowledge of our Dionysian essence can finally be expressed through the Apollinian song. The hidden knowledge in stories can finally be told and believed, and once again man can prepare for the onslaught of tragedy to come.

Make no mistake, this will not turn out well. Tragedies are stories of hubris and downfall. Regardless of the outcome of the looming War for the Dawn, our heroes will, one by one, end up destroyed or dead or devastated.

Which brings us to Jon Snow…

The Birth of Song

“He has a song,” the man replied. “He is the prince that was promised, and his is the song of ice and fire.”

His is the song of Dionysus and Apollo, and Jon Snow exhibits many of the characteristics of both parents, whether he realizes it or not. He is the archetypal son of myth.

A neat little thing about Jon Snow, which you’d come to learn if you were a regular listener to Radio Westeros as I am, is his keen perception of reality. More than any other character, and particularly within A Game of Thrones, he is shown to have noticed details that others had missed.

Our first encounter with Jon Snow occurs in the first chapter of AGOT. He cautions Bran to not look away during Lord Eddard Stark’s execution of the Night’s Watch deserter, and then he notices Bran’s reaction to the event. He observes the eyes of the deserter and makes an astute judgement of the man’s disposition, as he often does of many book characters. Jon was the one who noticed the sex of the direwolf pups and made the connection to his half-siblings. He also discovered the pup Ghost when he was overlooked by everyone else. Later at the feast, he thinks to himself, “A bastard had to learn to notice things, to read the truth that people hid behind their eyes.” He is the perspicacious Apollo reborn.

This is significant because the archetypal son as mythical hero is often associated with extraordinary vision. Marduk, the grandson of Apsu and the supreme god featured in the Enuma Elish of ancient Babylon, was said to have eyes all around his head. Horus, the son of Osiris, was depicted as keen-sighted falcon. It isn’t by accident that the rulers of these lands were representatives of these hyper-observant patron deities.

The all-seeing mythical hero has an advantage over friend and foe alike. They can judge character through the māyā of artificial persona. They can look into the past and the future, at least in a sense, and determine a the correct course of action. Sadly, they can also see the tragedy that will emerge but at least they can take steps to prepare for the disaster. This explains the sullen pragmatism in such a young man as Jon Snow.

But there is a mystical element too which comes from Jon Snow being a Stark. He has visions—dark visions—that fill him with dread and foreboding.

Before long he found himself talking of Winterfell.

“Sometimes I dream about it,” he said. “I’m walking down this long empty hall. My voice echoes all around, but no one answers, so I walk faster, opening doors, shouting names. I don’t even know who I’m looking for. Most nights it’s my father, but sometimes it’s Robb instead, or my little sister Arya, or my uncle…”

“Did you ever find anyone in your dream?” Sam asked.

Jon shook his head. “No one. The castle is always empty.” He had never told anyone of the dream, and he did not understand why he was telling Sam now, yet somehow it felt good to talk of it. “Even the ravens are gone from the rookery, and the stables are full of bones. That always scares me. I start to run then, throwing open the doors, climbing the tower three steps at a time, screaming for someone, for anyone. And then I find myself in front of the door to the crypt. It’s black inside, and I can see the steps spiralling down. Somehow I know I have to go down there, but I don’t want to. I’m afraid of what might be waiting for me. The old Kings of Winter are down there, sitting on their thrones with stone wolves at their feet and iron swords across their laps, but it’s not them I’m afraid of. I scream that I’m not a Stark, that this isn’t my place, but it’s no good, I have to go anyway, so I start down, feeling the walls as I descend, with no torch to light the way. It gets darker and darker, until I want to scream.”

This doesn’t sound like someone whose fate will turn out very well. Worse, he’s cognizant of this threat, yet he continues willingly down the dark depths all alone. This has all the hallmarks of a voluntary sacrifice motif. By connecting with these old gods, he understands clearly that he is living in a tragedy, whether he likes it or not.

This is perhaps why the old gods demanded blood sacrifice in front of the heart trees. The Dionysian old gods represent the ancient, inarticulate knowledge and wisdom lost in time. To access this information, one must be prepared to make a sacrifice of what you value most. It is a theme occurring again and again in ASOIAF and myriad other mythologies. It’s a pact to be made with the old gods (i.e. wisdom, society and our inner selves) that progress in the future can only be made when one gives up something in the present. Only when you are willing to make a sacred commitment to doing whatever it takes will you be able to bring about order from a corrupt chaos, or to depose a tyrannical order.

You forget about the meaning of this sacrifice at your peril.

Therefore, it’s not enough to pay attention to the Dionysian truths through your Apollinian lens. You must also articulate it and act it out through sacrifice. Throughout his narrative arc, Jon does both and thus demonstrates this commitment to his ultimate demise.

Ancient myths from around the world teach us about the importance not only power and brilliance in a leader, but of wisdom and sacrifice in the face of destruction, as a means of rejuvenating a society. Order becomes chaos, which begets new order, and so on. This is embedded in our DNA and environment, which is why it keeps recurring in our stories. Such is the tragedy of life.

Conclusion

The reason we read these stories though is to understand that we all go through these times. No one reading this has gone untouched by tragedy. Or, if you haven’t, you will. You or someone you love will undergo an awful event, or be stricken with illness of the body or mind. You may not have ice spiders climbing over your roof that’s buried with ten feet of snow, but you might lose your home in a natural disaster, or worse.

This is the truth of our reality. You may not avoid these disasters, but you will do far worse if you continue to delude yourself by denying otherwise. Mythological stories like ASOIAF are created to teach you both the inevitability of this reality as well as the importance of being the hero who responds to it competently.

Jordan B Peterson argues this in one of his lectures on the psychological significance of Biblical stories:

The stories remind us … Socrates believed that ‘all knowledge was remembering.’ He believed that the soul before birth had all knowledge and lost it at birth, and then experience reminded the soul what it already knew …

You’re not just a creature that emerged 30 years ago or 40 years ago; you’re the inheritor of three-and-a-half billion years of biological engineering. You have your nature stamped deeply inside of you, far more deeply than any of us realize. And when you come across these great stories, they are a reminder of how to be properly. They echo in your soul because the structure is already there. The external stories are manifestations of the internal reality, and then they’re a call to that internal reality to reveal itself.

I don’t know if George R.R. Martin ever read Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy. He’s more well-read than I and I wouldn’t put it past him, but it doesn’t really matter. Once he started borrowing mythological archetypes from other stories and incorporated them into his wondrous new world, he willingly participated in the grand process of delving into our deep consciousness for meaning and truth.

It may not have been Martin’s intention to call his story a “song” because of Nietzsche but it is no coincidence that he did, whether he knows it or not. When he was inspired to write this story, he became Apollo. He paid attention to his dreams and put them to paper:

It was the summer of 1991. I was still involved in Hollywood. My agent was trying to get me meetings to pitch my ideas, but I didn’t have anything to do in May and June. It had been years since I wrote a novel. I had an idea for a science-fiction novel called Avalon. I started work on it and it was going pretty good, when suddenly it just came to me, this scene, from what would ultimately be the first chapter of A Game of Thrones. It’s from Bran’s viewpoint; they see a man beheaded and they find some direwolf pups in the snow. It just came to me so strongly and vividly that I knew I had to write it. I sat down to write, and in, like, three days it just came right out of me, almost in the form you’ve read.

The lesson being taught implicitly in A Song of Ice and Fire is to stay alert, pay attention to the world around you, listen to your heart, and act in a way where you can be relied on when the shit hits the fan.

Be the song.

Nice entry!

The nisse in Scandinavian lore are associated with blot or sacrifice, usually at Yule when a ritual meal is set aside for them.

I never thought of the story being Dionysus/Apollo so much as Oak King/Holly King, which may not be so different. Lyanna definitely has Peresephone associations, but she is equally Helen of Troy and Robert’s Rebellion is a re-telling of the Trojan War.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the read. I like the idea of the nisse being directly associated with sacrifice, as that is clearly what happened to Nissa Nissa as well her archetypal representatives here.

Yeah, I definitely see Helen in Lyanna, and the Northern European mythologies in the symbolism with the oak tree, etc. GRRM likes to mix up the mythological symbolism with the various characters, even transforming their archetypes given the context. It’s really neat stuff.

What I hope to do is look at these specific mythical archetypes in ASOIAF and explain how they were interpreted in myth with respect to our own psychology. It should be a fun project.

Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not that much into Greek mythology. :)) I like your thesis, though, and it sounds like a VERY fun project. I’d like to add that another Persephone character is Arya–her moon associations are undeniable, and when she enters the House of Black and White, she is fully immersed in the Underworld. I always equated her with the Norse Hati (The Enemy, He Who Hates), who also has moon and ironwood associations, but Martin has done a fabulous job of layering mythical characteristics and archetypes into the characters.

What sources will you use?

What always bothered me about Nissa Nissa is this: in order to make a sacrifice meaningful, you don’t sacrifice that which you love the most. You sacrifice YOURSELF. You make yourself a Christ figure, which in essence is a dying/resurrecting nature god theme yet again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

GRRM mentions in the preface to ‘RRetrospective’ that he’d studied Norse Mythology and Literature during his years at college. Especially Eddas.

https://theambercompendium.wordpress.com/2017/01/22/encyclopedia-of-myth-in-asoiaf-house-wynch-of-iron-holt/

LikeLiked by 1 person

“My major was journalism, but I took a minor in history. My sophomore year I signed up for the History of Scandinavia, thinking it would be cool to study Vikings. Professor Franklin D. Scott was an enthusiastic teacher who invited the class to his home for Scandinavian food and glug (a mulled wine with raisins and nuts floating in it). We read Norse sagas, Icelandic eddas, and the poems of the Finnish patriotic poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg. I loved the sagas and the eddas, which reminded me of Tolkien and Howard, and was much taken with Runeberg’s poem “Sveaborg,” a rousing lament for the great Helsinki fortress “Gibraltar of the North,” which surrendered inexplicably during the Russo-Swedish War of 1808. When it came time to write term papers, I chose “Sveaborg” for my topic. Then I had an off-the-wall idea. I asked Professor Scott if he would allow me to submit a story about “Sveaborg” rather than a conventional paper. To my delight, he agreed. “The Fortress” got me an A … but more than that, Professor Scott was so pleased with the story that he sent it off to The American-Scandinavian Review for possible publication.”

(George R.R. Martin)

LikeLike

“What always bothered me about Nissa Nissa is this: in order to make a sacrifice meaningful, you don’t sacrifice that which you love the most. You sacrifice YOURSELF. You make yourself a Christ figure, which in essence is a dying/resurrecting nature god theme yet again.”

Yes, I agree with that. It might look a bit like Abraham sacrificing Isaac, but I suspect that Nissa Nissa was a little more of a willing participant. After all, if she was Azor Ahai’s wife, how could she not see what she did to that poor lion the last time around? So that’s where I differ a little from LmL, who thinks Azor Ahai is a more monstrous villain, whereas I think of him as a tragic figure.

LikeLike

@lordbluetiger:

I’m not surprised that Martin studied Norse mythology. It smacks you in the face, starting with the series title and the book titles. :))

The two most interesting and useful classes I ever took were World Mythology and Science Fiction/Fantasy Literature. Anyone who loves to read should at least take a mythology class. You get so much more out of what you read.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As I was reading this I kept thinking to myself, “this is exactly what I would expect a Jordan Peterson lecture on ASOIAF to sound like.” And then you name-dropped him and I couldn’t stop grinning like a fool!

Very interesting read. It makes sense to me that GRRM got the archetypes “right” so to speak.

LikeLike

Yeah, he’s inspired me big time. I’m trying to get to know myself by treating ASOIAF as literature and seek out the archetypes and psychological themes using the same method. It’s gotten me reading so much that’s out there.

As you can see, I have Nietzsche and a bit of Northrop Frye here, but I’m studying Jung and Eliade now. There’s so much material to work from. With the revelation that GRRM had been seeding his books with these archetypes, and that I’ve read ASOIAF numerous times already, I’ve found a neat little niche of scholarship that no one has really delved into yet.

There are also plenty of parallels in the Bible too, which I’m going to get to in due time. I have about five or six more essays started right now, so I need to pick one and focus on it.

LikeLike

Cool, I’m really looking forward to reading more man!

LikeLike

(your other posts make it obvious that you’re familiar with JBP but this was the first post I read on this site, found it on reddit!)

LikeLike

It’s really amazing how many people have discovered JBP. He’s a phenomenon.

LikeLike

Who? LOL

I think I’m getting old. I just looked him up and he isn’t much older than I am. When I was in school it was Joseph Campbell, Freud and Jung! I still have my old tattered copy of Hero with a Thousand Faces and Frazer’s The Golden Bough.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think that it’s nearly 100% that GRRM has read ‘The Golden Bough’, since we get customs very similar to the ‘Sacred King/Corn King’ motif in ASOIAF (namely Pentos). It’s worth to mention that both C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien have read Frazer, and discussed it together with several other writers. In fact, Tolkien’s arguments about Frazer’s discoveries helped to convince Lewis to become a theist.

Lewis even wrote:

“Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the others are men’s myths: i.e., the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call ‘real things’.”

And Tolkien believed that:

“We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can Man aspire to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall. Our myths may be misguided, but they steer however shakily towards the true harbour, while materialistic ‘progress’ leads only to a yawning abyss and the Iron Crown of the power of evil.”

And

“After all, I believe that legends and myths are largely made of ‘truth’, and indeed present aspects of it that can only be received in this mode; and long ago certain truths and modes of this kind were discovered and must always reappear.”

Bascially, he thought that mythology and ‘pagan’ cultures shouldn’t be dismissed, because there’s much we can learn from them. And he said that mythology was a way to preserve ‘symbolic’ and ‘religious’ thinking in humans, before humanity was ready for the ‘true’ religion. ‘

Lewis agreed:

”Now as myth transcends thought, incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the dying God without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens – at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle. I suspect that men have sometimes derived more spiritual sustenance from myths they did not believe than from the religion they professed. To be truly Christian we must both assent to the historical fact and also receive the myth (fact though it has become) with the same imaginative embrace which we accord to all myths. The one is hardly more necessary than the other is.”

So, in a nutshell: any kind of symbolic thinking is better than pure materisalism. Because pure materialism leads to things like Tywin using machiavellian logic to justify his war crimes and the Red Wedding. Materialism leads to people like Azor Ahai and Bloodstone Emperor, to Roose, Ramsay and Euron… To ‘The Iron Crown’ as Tolkien would say.

LikeLike

Well, Lewis says Christ was historical, but since that’s never been proven, he is for me relegated to the mythological. (I think he was a real person, but Paul turned him into a god.) Tammuz, Mithras, Osiris, Balder. He is a nature god just like them. Conceived and died at the spring equinox according to the Bible and born at the winter solstice. His cousin John the Baptist was born at the summer solstice (the Feast of St. John) and killed by Salome at the autumnal equinox.

These myths resonate with us at our very pith and core. It’s part of who we are and it’s embedded in our psyches. Writers like Tolkien, Lewis, the other Inklings along with modern writers like Martin understand this. Screenwriters get it too. It’s why Star Wars is still so popular. Joseph Campbell once said that Lucas was the best student he ever had.

Where Martin and Lucas differ from Tolkien and Lewis is in their inclusion of strong female characters. The myths had them too, but that very Christianity they praise to the skies gave them a disdain for and fear of the feminine and women. The ancients revered the feminine, and before Christianity came along women were much more equal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In regards to Lewis this might be true, but ‘The Silmarillion’ has plenty of female characters… Galadriel, Luthien (actually, when you look at the tale of Beren and Luthien, Beren doesn’t do much and she has to save his *** – she defeated Sauron in a magical duel while the future Dark Lord was Morgoth’s second-in-command, she helped recliam SIlmarill from Morgoth etc.), Queen Melian of Doriath, Elwing, Nienor, Lady Morwen (really similar to Catelyn Tully btw), Arien, the goddess of Sun in Middle-Earth, and also defeated the Dark Lord Morgoth, (Balrogs, like the one who killed Gandalf in Moria were related to her, as they were fire spirits as well), Haleth who was Chieftain among the Men in the First Age and founded House of Haleth, Varda, Yavanna & other Valier, Uinen, the sea goddess, Erendis from ‘Aldarion and Erendis’ novella, and many others…

But yeah, besides Jadis the White Witch, Susan, Lucy, Arawis from Narnia Book IV, and Green Witch from ‘Silver Chair’ I can’t even name more women from C.S. Lewis’ books.

LikeLike

Tolkien wrote about women, but other than Eowyn and Galadriel, none of them are really pivotal to the story, although Luthien was bada**. Much of that backstory fleshed out and matured later, and Christopher Tolkien edited his father’s papers heavily. Within the scope of Lord of the Rings, Eowyn is seriously flawed (and a much better match for Aragorn than Arwen), and only Galadriel really shines. Lewis’ treatment of women was downright misogynistic. Poor Susan, not allowed to enter heaven because she was interested in boys and started wearing makeup. There’s nothing worse than a reformed (enter bad habit here), and Lewis was an atheist for most of his life. When he took up Christianity, he did so with a vengeance. He was also a racist, but that’s another topic. Let’s be clear: Lewis was no brilliant mind. Chronicles of Narnia is social and religious indoctrination of the worst kind.

Maybe they’re partly a product of their times, although it’s not hard to imagine Lewis on Fox News or Rush Limbaugh prattling on about the virtues of social conservatism and political correctness. Tolkien is forgiven simply because the world he created was vast and colorful, even if not without its flaws.

I think this is why I liked His Dark Materials so much. It’s the anti-Narnia, and its heroine isn’t a little goody goody. She’s the second Eve, but she isn’t the source of all evil and sin. She’s the source of all knowledge and wisdom.

Did you see in the news last week that the famous Viking warrior that was dug up about 40 years ago was a woman? Take that, CS Lewis.

Martin is very refreshing. At this point in the story, it’s the women who are calling the shots and are by far the most powerful characters in the books, although they are just as flawed as the men. Cersei, Dany, Val, Arya, the Manderly girls, Asha, Genna Lannister, Ellaria Sand, Arianne Martell, Alys Karstark, Lady Dustin, Melisandre, Dalla, Lyanna, Catelyn, the Mormont women, the list goes on. Even little Melisandre and Lyanna Mormont are tough cookies, and with the exception of Dany, Cersei and Catelyn, they all have sense. (That’s just my opinion, by the way. Catelyn and Sansa are my two least favorite characters.)

LikeLike

The point of Nietzsche’s thesis outlined above was that we abandon spiritual transcendence at our peril, including religious devotion. As such, I respect the likes of Lewis, as he actively sought the higher mysteries through an appreciation of mythology and then, as he matured, he returned to Christianity. He came about it honestly, and his letters and published works clearly demonstrate an inquiring mind. I also loved the Narnia books as a child, so perhaps I’m biased, but I came to appreciate his Christian apologetics work too.

I’m more than fine with Martin developing a huge number of female characters who can represent the wide variety of archetypes, which also functions as a social commentary on the role of feminism in his world and our own. That said, I don’t want to dismiss works from past thinkers on the basis of our modern perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just finished your second essay and I really liked it. You hit on something here that does seem intentional although like you said it is hard to know for sure. Rhaegar is an Apollo figure and I have not seen a good reason for it until here. Especially if I am right and he is a Morningstar and not a sun he should not be Apollo just as a reference to the sun and since he is there must be another reason. George is using a sort of yin-yang balance theme and order and chaos is part of it this looks like where he may be going for his version of it. The mystery religions and Azor Ahai Reborn as Horus are things I am onto and writing about, you have already hit on.

I wonder if there are other places we can look for Dionysus and Apollo. Tyrion and Tywin come to mind. Tyrion is a drunk sex loving Dionysus type while Tywin is a logical solar person, at least on the surface. In typical GRRM fashion Tyrion is also logical and Tywin is secretly pretty carnal so the conflict is internal as well as external.

Anyway, great stuff. This is exactly the sort of thing I am not good at. I can see superficial mythical parallels like fertility vs death or Morningstar vs sun and spot them in the books pretty well. This is deeper and much needed. I also agree with the above that Azor Ahai was a tragic figure who was only a villain toward the end or maybe in the middle, not sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My essay supports viewing Rhaegar as a Morningstar archetype. Like Apollo, Lucifer is the manifestation of reason and vision. In fact, given that Apollo is actually the god of light rather than the sun itself (Helios defers to Apollo), this only goes to provide a stronger basis for Rhaegar as Morningstar Apollo in this lens.

And, yes, Tyrion is certainly a Dionysian, though I would have Jaime as the Apollinian. Tywin is more of a Zeus, the dominating deity of order.

The irony is that Tyrion views himself as Apollo through his study of books and appreciation of the Westerosi arts of science and medicine. He masks his Dionysus with this Apollinian approach, but discovers that he fails to achieve proper individuation (the mature psyche developed through the emergence of consciousness), which turns him into a cynical nihilist. Thus, he embarks on a darker journey. His fool’s motley is but a prelude to the emerging monster, a small man with a big shadow, snarling in the midst of all.

The same could go for Azor Ahai. His pride and arrogance are the result of the man’s Jungian shadow emerging, which makes him the ultimate tragic villain in the ASOIAF proto-historical myth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Cosmic Tree in ASOIAF | Plowman's Keep